QUESTIONING EQUIANO

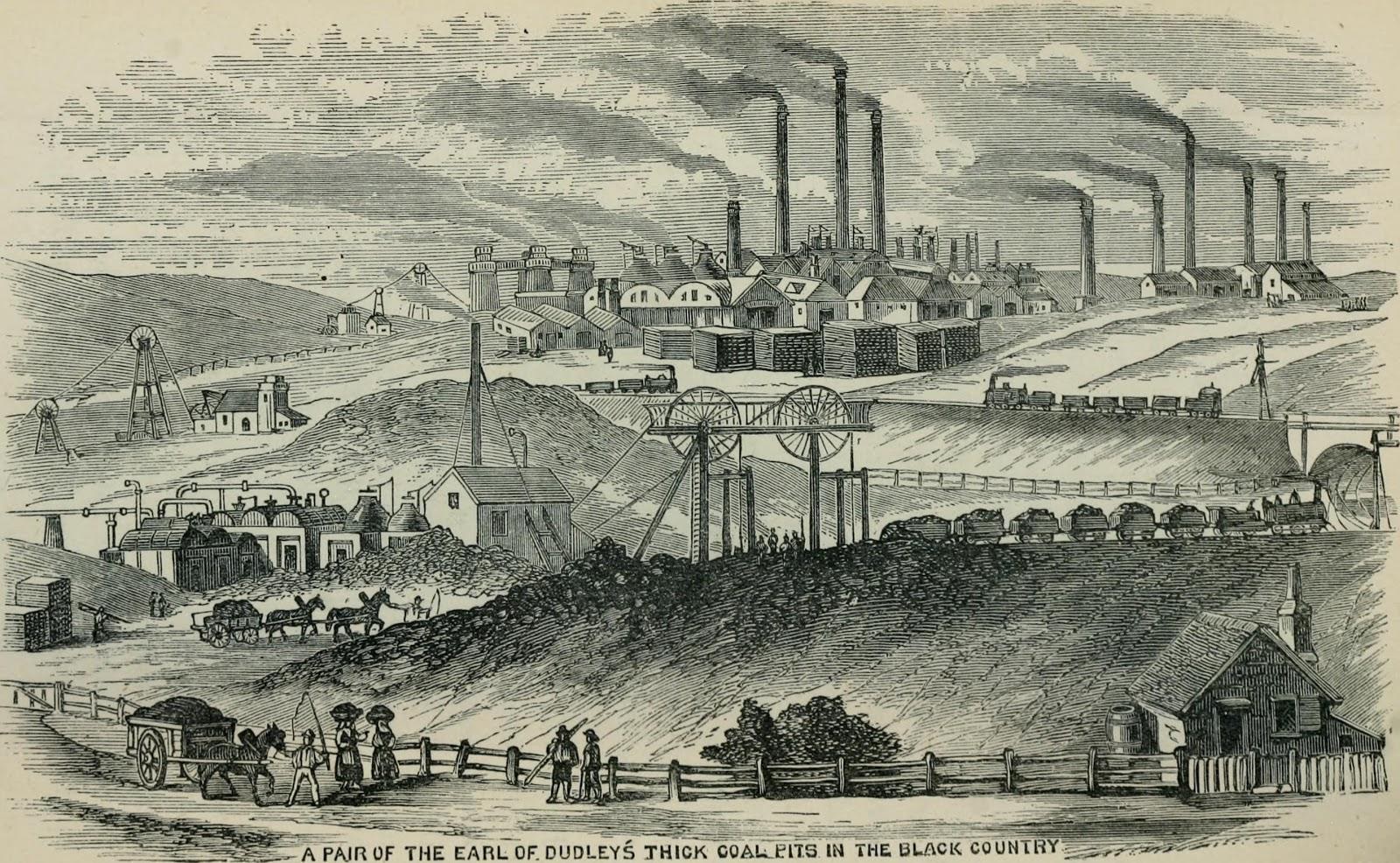

Numerous questions have arisen in terms of what Gustavus Vassa knew, what he did, and what he thought. This section includes a discussion of where Vassa was born, the significance of his name, Igbo scarification and body markings, slavery and trade in Igboland, Vassa's views of slavery and his attitudes toward race and culture. There is also discussion of Vassa's relations with scientists and the industrial revolution, his recognized and unrecognized involvement in the abolition movement, and his connections with the Mosquito Shore of Central America and with Sierra Leone. Finally there are discussions of Vassa's relationship with German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and Vassa's legacy today.