Significance of his Name

Gustavus Vassa received the name Olaudah Equiano when he was an infant. As he notes in his autobiography,

...our children were named from some event, some circumstance, or fancied foreboding at the time of their birth. I was named Olaudah, which, in our language, signifies vicissitude or fortune also, one favoured, and having a loud voice and well spoken. I remember we never polluted the name of the object of our adoration; on the contrary, it was always mentioned with the greatest reverence; and we were totally unacquainted with swearing, and all those terms of abuse and reproach which find their way so readily and copiously into the languages of more civilized people.The only expressions of that kind I remember were ‘May you rot, or may you swell, or may a beast take you.’

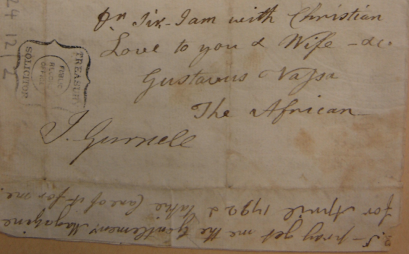

He did not comment on the second part of his name, Equiano, which was certainly not a surname, since Igbo culture did not use surnames, but rather an elaboration on the name Olaudah. His birth name, Olaudah Equiano, was useful in establishing his credentials as African because his authority rested on his African birth, his kidnapping, and his endurance of the Middle Passage. Nonetheless, from when he was about 12 years old in 1754 until his death in 1797, he was known in public and in private as Gustavus Vassa. After 1786, he usually identified himself in print as Gustavus Vassa, the African, but rarely by his birth name. As author and prominent abolitionist he identified by the name that he was known, that is, Gustavus Vassa, not Olaudah Equiano. ‘‘Vassa’’ was the name legally assigned to him by the British Empire (this was his name on his manumission papers as well). And as a British citizen, now free with the papers to prove it, he was willing, for protection, convenience, and consistency, to go by Vassa, but this may have had something to do with the restraints in which he had to live and survive in a country in which slavery was still legal. Vassa was additionally assigned other names; during the Middle Passage, he was known as Michael, while in Virginia he was called Jacob, before finally being named Gustavus Vassa as he was being taken to England. Hence It was who gave him the name Gustavus Vassa, which name Vassa later protests that he initially rejected, despite punishment.

According to the first edition of his autobiography,

While I was on board this ship [the Industious Bee], my captain and master [Pascal] named me Gustavus Vasa. I at that time began to understand him a little, and refused to be called so, and told him as well as I could that I would be called Jacob; but he said I should not, and still called me Gustavus; and when I refused to answer to my new name, which at first I did, it gained me many a cuff; so at length I submitted, and was obliged to bear the present name, by which I have been known ever since.

The choice of the name Gustavus Vassa seemed to have been prophetic, at least to Vassa later in his life, although it is still unclear why Captain Pascal selected that name of all names to call his newly purchased slave in 1754. Vassa's namesake was none other than the Swedish national hero, Gustavus Vasa (1496-1560), king of Sweden (1523-1560), founder of the modern Swedish state and the Vasa dynasty. Known as Gustavus Eriksson before his coronation, King Gustavus I was the son of Erik Johansson, a Swedish senator and nationalist, who was killed in the massacre at Stockholm in 1520, under the orders of King Christian II of Denmark, who was attempting to assert his control over Sweden through the Kalmar Union. Gustavus was imprisoned but escaped to lead the peasants of Dalarna to victory over the Danes, being elected protector of Sweden in 1521. In 1523 the Riksdag at Strangnas elected him king, ending the Kalmar Union that King Christian II of Denmark had been attempting to enforce. Two centuries later, English playwright Henry Brooke recorded these heroic deeds in his play, Gustavus Vasa, The Deliverer of his Country, published in 1739. Prime Minister Walpole banned the play for political reasons and it was not actually staged legally in London until 1805. And undoubtedly it was performed in London, and it was performed in Dublin in 1742 as The Patriot. Brooke's play was republished in 1761, 1778, 1796, and 1797. Hence the Swedish name had political significance in England that explains some association between Vassa and his namesake but does not explain why Pascal settled on the name in 1754.

In his adult life, and indeed since at least his baptism in 1759, he only went by the name of Gustavus Vassa, and when he used his birth name it was always an addition, just as the reference to himself as African was sometimes used. In public references, moreover, only one example of a reference to him only as Olaudah Equiano has been uncovered among more than 100 newspaper references, and that reference relates to a meeting that he attended to raise funds for and acknowledge the importance of Thomas Hardy, the founder of the London Corresponding Society who had been charged and acquitted of treason. The meeting was held in the fall of 1796, several months before Vassa's death in February 1797. He was actually not allowed to speak at the meeting, but the event was recorded a year later, some six months after he had died.