Portraits - Real or Not

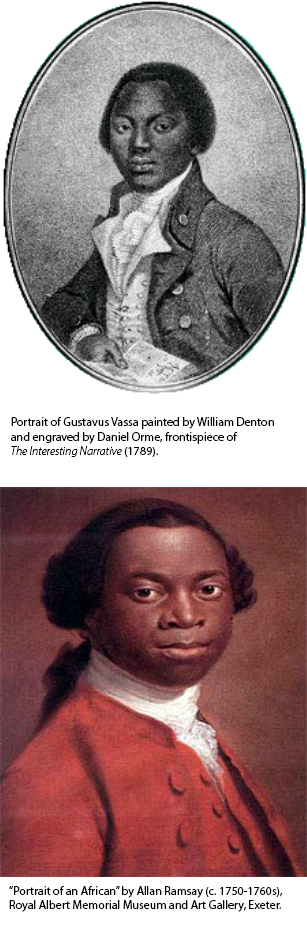

There are two famous portraits supposedly of Gustavus Vassa. The first is the frontispiece of Vassa’s autobiography painted by William Denton and engraved by Daniel Orme, which is clearly Vassa. The second portrait that has often been represented as being Vassa is the oil painting by Allan Ramsay (1713-1784) in the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Art Gallery in Exeter. While the frontispiece portrait is most definitely of Vassa, the second is not. The oil painting was originally identified as “Olaudah Equiano” and is one of the few portraits of Africans portrayed in a gentlemanly manner rather than as an enslaved person or servant and is titled “Portrait of an African.” It is now considered most likely an 18th century portraiture of Ignatius Sancho, the Afro-Briton composer, actor, and writer.

Percy Moore Turner, a London-based art dealer, gave the “Portrait of an African” to the Exeter museum in 1943. It was initially titled “Black Boy by Joshua Reynold’s.” In 1961, William Fagg, a curator at the British Museum, suggested that the sitter was Olaudah Equiano, based on its supposed resemblance to the portrait of Vassa from his frontispiece. While his name continues to be connected with this portrait, most scholars agree that this is not Vassa. In the frontispiece, Vassa is presumably middle-aged. Some have suggested that the oil painting could depict a younger Vassa. John Madin, who has written on the topic, suggests that aging cannot explain the visible differences in the sitters’ jaw-lines. The facial likeness is not there. Further, the sitter in the oil painting is dressed in clothes that were fashionable in the late 1750s or early 1760s. The style of the painting aligns with that of other portraits that Ramsay produced from 1750 to the 1760s. During this time, Vassa would have been no older than someone in his early twenties. He did not achieve emancipation until 1766. It is unlikely that, while enslaved, he would have had the means to dress in such gentlemanly attire or have had the opportunity to pose for a portrait. Moreover, during much of this time of his life, he was most often at sea with his slave masters, Michael Henry Pascal before 1763 and Robert King in the Caribbean for several years thereafter.

Madin suggests the painting is likely of a wealthy man in his 20s or 30s. In the 1750s and 1760s, high-status society portraiture was quite costly and likely out of reach for most individuals, let alone those who were enslaved. This lends support to the notion that the sitter was Ignatius Sancho, who was older than Vassa and therefore, of the correct age range for the portrait. He associated with the literary, artistic, and aristocratic elite of London. He worked as a servant for one of the wealthiest aristocratic families in England. In 1751, the Duchess gave him £70 as well as provided him with £30 annually. His master was an ardent art collector and regularly contracted contemporary artists. This combined with his gentlemanly status makes Sancho a likely candidate for Ramsay's portrait. While there is sufficient evidence to suggest that the sitter was Sancho, compared to a portrait by Thomas Gainsborough of Bath in 1768, the likeness of Sancho in both portraits is not immediately recognizable. A possible explanation for this is that Sancho's health had deteriorated over the decade or more between the two portraits.

Other scholars, such as Christopher Fyfe, have suggested that the portrait may be of Ottobah Cugoano, another famous Afro-Briton writer and a friend of Vassa. Cugoano, like Vassa, was too young to be the sitter in the portrait, however. Cugoano was born in 1757 and was sold into the slave trade in 1770. He did not earn his freedom until after 1772. It has also been put forth that the portrait may be of an African prince named William Ansah Sessarakoo. Sessarakoo came to England to receive an education. Instead, he was sold into slavery. He came under the protection of the Earl of Halifax and became well known in England. He was painted by artists like William Hoare and Gabriel Mathias. Nonetheless, it could not be him as he returned to West Africa in 1750.

Prior to the discovery that it was Allan Ramsay who had painted the portrait, the painting was attributed to Joshua Reynolds. This raises two more potential subjects, Reynold’s personal black servant or Samuel Johnson’s servant Francis Barber. Comparing this portrait with that of a later portrait Reynold painted of his servant suggests they are not the same man. Brycchan Carey an academic specializing in the history of slavery and abolition in the British empire, proposes that it is more likely to have been a portrait of an ordinary person who was hired as a model. The Royal Albert Memorial Museum has no fixed position on the “correct” subject of the work.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carey, Brycchan. “The Equiano Portraits," BrycchanCarey.com, published April 2002.

King, Reyahn. “Ignatius Sancho and Portraits of the Black Elite,” In Reyahn King, Sukhdev Sandhu, James Walvin and Jane Girdham, Ignatius Sancho: An African Man of Letters (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1997), 15-43.

Madin, John. “The Lost African: Slavery and Portraiture in the Age of Enlightenment,” Apollo: the International Magazine of Art and Antiques (August 2006), 34-39.

“Portrait of an African, probably Ignatius Sancho, once identified as Olaudah Equiano,” Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery - Exeter City Council, accessed March 27, 2020.