Ambrose Lace

Ambrose Lace intersected with Gustavus Vassa in two ways, although they probably never actually met. Lace was one of the most prominent slave traders and merchants in Liverpool in the last half of the 18th century. Lace operated to the Bight of Biafra, first as a ship captain on the Edgar and then as an investor in slaving voyages. His business was centered at Calabar on the Cross River, which at the time was one of the primary ports from which enslaved Africans left for the Americas, Calabar, which today is the capital of Cross River State in Nigeria, is located in what Europeans referred to as the lower Guinea coast, separated from the Bight of Benin by the Niger River Delta. The merchants that dominated the trade in this area were predominantly from Bristol and Liverpool, as was Lace. Lace's commercial dealings were the first of his connections with Vassa, who would have become aware of the activities of the major slave traders in the course of his increasing interest in combating the slave trade. Vassa's second connection with Lace, and indeed other prominent slave traders, was through the Parliamentary inquiry into the slave trade that began in March 1789 and continued over the next couple of years. Vassa regularly attended those sessions and would have witnessed Lace's testimony and heard his account of the slave trade and events in the Bight of Biafra. Based on Lace's surviving correspondence, none of which Vassa ever saw, it is clear that Lace perjured himself before Parliament in relation to his involvement in the terrible massacre at Calabar in 1767. Lace was clearly one of the leading conspirators in that incident, but he denied before Parliament that he knew anything about it. Without doubt, his testimony and that of other slave traders was the subject of extensive discussion and debate in the pubs and coffee houses of London. Vassa's interest in abolition makes it certain that he would have been aware of these discussions and most likely participated in them.

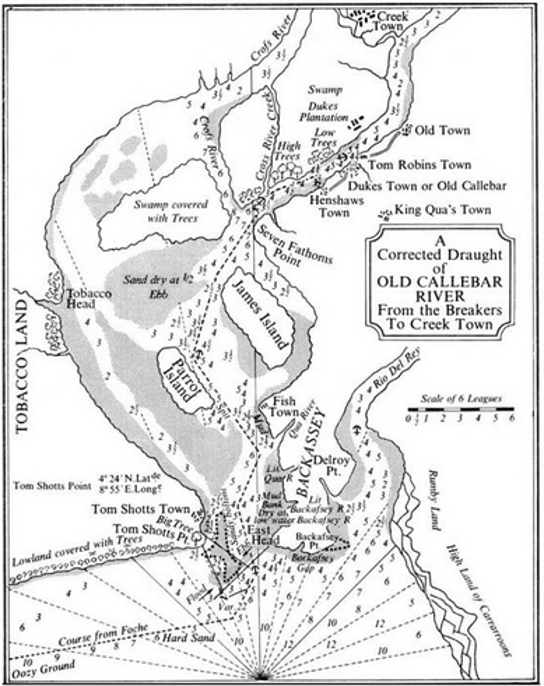

By the 1760s, the two most important wards in Calabar were Old Town and Duke Town. Old Town was led by the Robin John family which had established strong ties to English merchants and was strategically located on the Calabar River, the main tributary of the Cross River, at the narrowest point so that all traffic passing along the river could be taxed. The family was a relentless supplier of Africans who had been captured for the British ships that ventured to the Cross River. Other wards of Calabar were also active in the trade, especially Creek Town, located further inland in the Cross River Delta on Creek River. Duke Town or New Town was situated on the Calabar River at the confluence with the Cross River and was under the leadership of the Duke family. The two commercial houses of the Robin John family and the Duke family became fierce competitors, each collecting different taxes and tolls on visiting European ships and attempting to secure a monopoly position in the trade.

In June 1767, Ambrose Lace was involved in what became known as the massacre at Old Calabar. At the time, European merchants referred to the town as "Old Calabar" rather than simply Calabar to distinguish the place from Elem Kalabari in the Niger Delta, which Europeans called New Calabar. The two ports had no connection other than the European nomenclature. In a bid to intimidate their adversaries, the Old Town traders kidnapped a prominent Liverpool ship captain and held him hostage for 29 days until he agreed to pay a hefty ransom. Infuriated, the merchant refused to engage in any further business with the Robin Johns family. The captains of the English ships then conspired with the Duke family to attack their Old Town adversaries, inviting them to board the English ships, and then ambushing them. 300-400 men from Old Town, led by Amboe Robin John, Little Ephraim Robin John, and Ancona Robin Robin John, rowed to the English ships in ten canoes. Amboe, Little Ephraim, and Ancona first boarded the Indian Queen, where they stayed the night. The next morning, Captain James Bivins arranged for the Africans to deliver a letter to Ambrose Lace. From there, they took letters to Captain James Maxwell, Nonus Parke, and Bivins. When the Robin Johns boarded Bivins’s boat, Lace instructed Bivin and his men to lock the men in the ship cabin. The crewmen, and all of the other ships, aside from the Edgar and the Concord, opened fire on the Old Town canoes. The Duke Town traders joined in the attack. Amboe was subsequently beheaded. Little Ephraim and Ancona were captured and taken prisoner. Along with 336 other enslaved Africans, the men endured the 45-day Middle Passage to the island of Dominica. Only 272 survived the journey. They were later resold into slavery in Virginia.

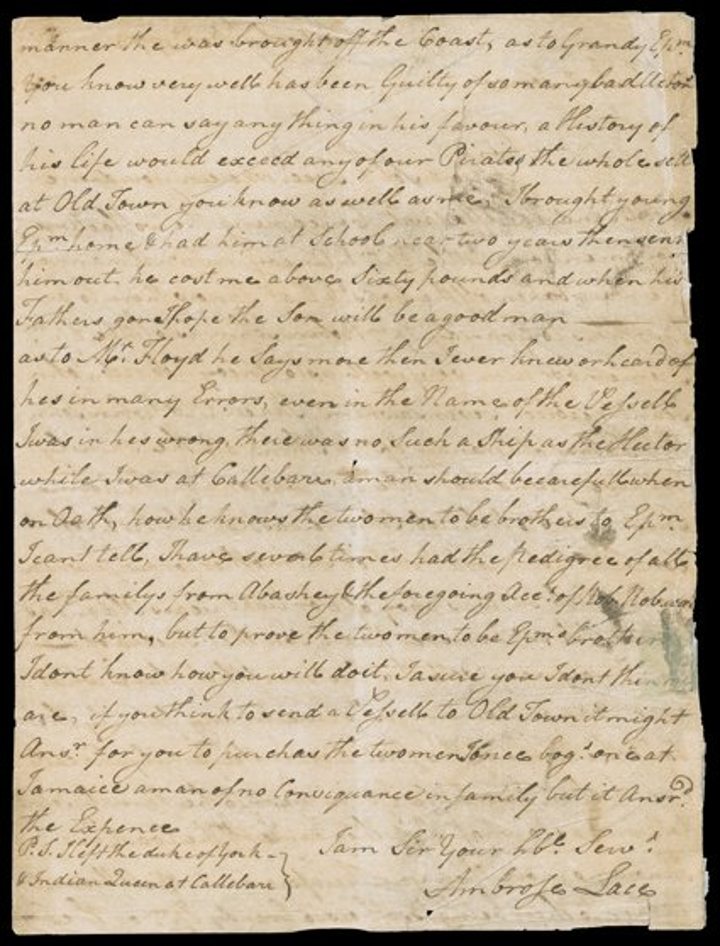

Little Ephraim and Ancona wrote numerous letters to slave traders involved in Calabar, pleading for their assistance in escaping. That included Ambrose Lace who had participated in the massacre, and most certainly helped to organize it. Perhaps hoping to atone for his sins or perhaps to secure a future trading partner, Lace looked after another member of the family, Robin John Otto Ephraim, in Liverpool. He enrolled him in school for two years before sending him back to Calabar. Lace considered the boy his protégé, hoping that “when his Fathers gone…the son will be a good man,” that is be his agent in Calabar.

The case of the massacre at Old Calabar came to the attention of various abolitionists in England, including Thomas Clarkson, while Chief Justice Lord Mansfield, who had issued the landmark ruling in the Somerset vs. Steward case of 1772, became involved in the efforts to free the men. On October 14, 1774, Little Ephraim and Ancona finally sailed for Old Calabar. Following multiple petitions and the efforts of British abolitionist, Clarkson convinced Members of Parliament in the House of Commons to launch a hearing into the massacre at Old Calabar in 1790. Lace was questioned during this time and denied involvement, which his surviving correspondence contradicts. He describes the chain of events leading up to the massacre in the following way:

The principal people from Old Town came on board my ship, where the duke (the principal man of Old Town) was to have met them; they came on board about half past seven in the morning; at about eight I was going to breakfast with a person who called himself the king of Old Town; there were four of the king’s large canoes alongside of my ship, where the other canoes were I cannot tell: I was just pouring out some coffee, when I heard a firing. I went upon deck along with the king, and my people told me my gunner was killed; immediately the king was for going overboard; I then told him to stay where he was; he told me he would not, he would go in his canoe, which he did; his son who was with him in my ship he left behind, but called to him in his own language to stay with me, which he did; the firing, by what I can recollect, might be for ten or fifteen minutes, but I cannot be certain as to the exact time. The canoes were most of them then got astern of my ship within about 300 or 400 yards; I had not time to make observations of the two parties, I wanted to defend myself after I was fired into; I was no further molested, the canoes were all gone.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

This webpage was

last updated on 2020-08-20 by Carly Downs