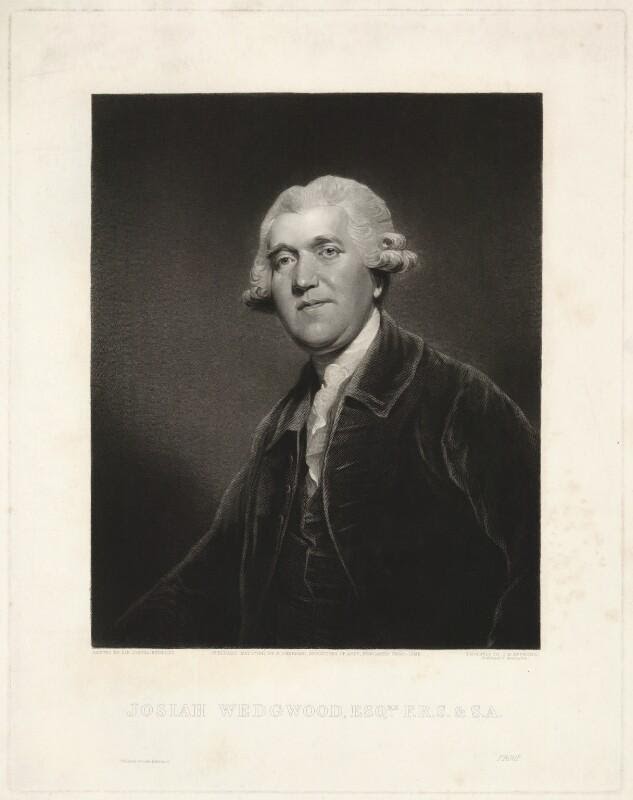

Josiah Wedgwood

(1730 - 1795)

Josiah Wedgwood, born in Burslem, Staffordshire, England, likely on July 12, 1730, was a master pottery designer and producer, and was one of Gustavus Vassa's first subscribers. Wedgwood came from a line of potters dating back to the early 17th century. In his early life, he showed great promise of becoming a potter himself; however, after contracting a serious bout of smallpox, Wedgwood’s knee had to be amputated. This disabled him from using the potter’s wheel, an essential tool in pottery making. As a result, he focused his attention on enriching his knowledge in pottery and its designs. In 1754, he became an apprentice to renowned potter, Thomas Whieldon, thus allowing him to master his pottery and design skills. In 1759, he founded a company that manufactured and produced fine china and pottery for a market that had developed for luxurious art pieces. Consequently, the Wedgwood company saw swift success and soon became a leading pottery vendor in England.

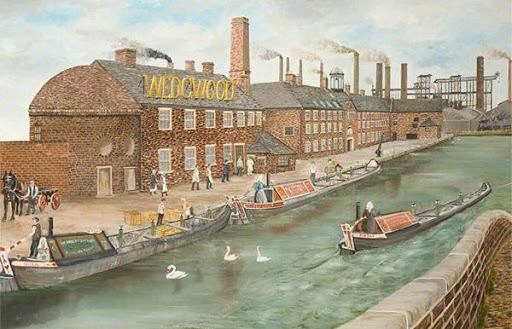

Wedgwood had a reputation for being an aggressive and imaginative salesman. As a result of his superior marketing and craftsmanship skills, he became the official potter of Queen Charlotte of England in 1762. He also worked for other distinguished nobility such as Empress Catherine II of Russia. He was known for treating his employees well, as he “provided healthcare, housing and schooling for his workers and their families” (Carretta, p. 253). He even built a village for his workers, which he called Etruria. The housing accommodated 300 employees at a cost of £3 per year to rent. In 1764, Wedgwood married his third cousin, Sarrah Wedgwood (1734 – 1815). Together they raised eight children. His first daughter, Susannah Wedgwood (1765 – 1817) married the son of Wedgwood’s partner. The couple gave birth to Charles Darwin, who subsequently became one of the most famous naturalists of his time.

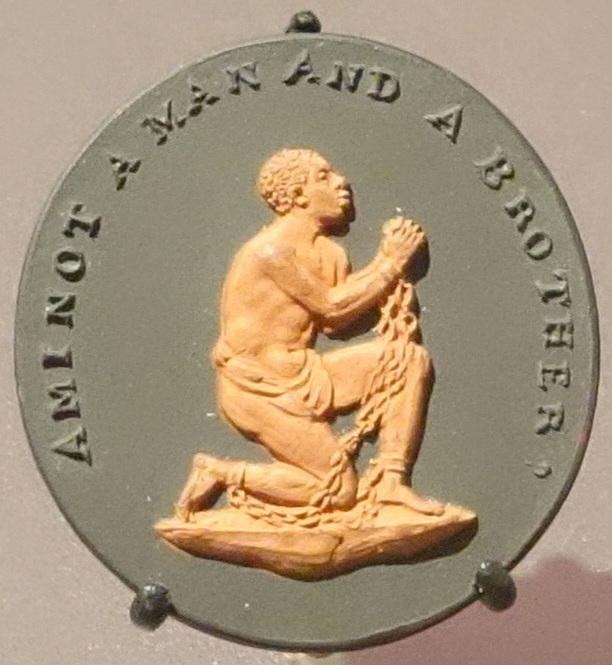

James Phillips, the book publisher, who knew Wedgwood through a business affiliation, recruited Wedgwood to design a medallion that became the symbol of the abolitionist movement. Phillips was a Quaker and one of the twelve founding members of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST). The organization’s founders included Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson. Phillips recommended that Wedgwood design an official medallion for SEAST, which subsequently was widely distributed. The medallion depicted an enslaved Black man in chains on his knees against a white background, with the words “Am I not a Man and a Brother?” Wedgwood mass produced the medallion which appeared on posters, pins and even tobacco pipes.

Phillips also introduced Vassa to Wedgwood. SEAST endorsed Vassa's autobiography, inviting him to lecture at different events in Britain. Many members of the society became subscribers to Vassa’s Interesting Narrative. In November of 1788, Vassa wrote to Wedgwood on a printed solicitation for the Interesting Narrative asking him to buy his soon to be published autobiography. The handwritten note indicates that Vassa and Wedgwood were well-acquainted, as he calls Wedgwood “worthy sir” and amongst his “worthy friends.” The solicitation also marked the first known time that Vassa publicly referred to himself as “Olaudah Equiano.” On August 21, 1793, Vassa wrote to Wedgwood again, asking him for protection on his trip to Bristol, where many people opposed the abolition of slavery. A few years earlier, abolitionist, Thomas Clarkson, had visited Bristol with a bodyguard, as he too anticipated opposition from the pro-slavery community. Vassa also feared that, as an experienced seaman, he would be forced into joining the Royal Navy in Bristol due to the ongoing war with France. Wedgwood was out of town and replied to the letter three months later. He told Vassa that he should contact his secretary, his nephew, while he was away and signed the letter “your friend and servant.” Vassa did not actually need Wedgwood’s help, as he did not encounter any difficulties in his journey.

In his later years, Wedgwood invented a device that could measure oven temperatures and became a fellow of the Royal Society in the United Kingdom. When he retired in 1790, he gave the Wedgwood company to his sons, which became Josiah Wedgwood and Sons Ltd. His sons maintained his legacy by continuing to be the leading pottery manufacturers in England. In 1795, Josiah died in the house he built on the grounds of Etruria. He left his fortune to his children. His cause of death is thought to have been cancer of the jaw.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent, Equiano the African, Biography of a Self-Made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

McKendrick, Neil, "Josiah Wedgwood and Thomas Bentley: An Inventor-Entrepreneur Partnership in the Industrial Revolution," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 14 (1964), 1-33

Ramage, Nancy Hirschland, “The English Etruria: Wedgwood and the Etruscans,” Etruscan and Italic Studies 14:1 (2011), 187-202.

Reilly, Robin, “Wedgwood, Josiah (1730-1795), Master Potter,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004.

Gustavus Vassa to Josiah Wedgwood, Handwritten Note on Printed Solicitation for the Interesting Narrative, November 1788, L74/12632, Wedgwood Museum, Barlaston, Staffordshire.

This webpage was last updated on 2020-08-25 by Kartikay Chadha