Britain in the Late 18th Century

Britain the late eighteenth century was defined by its emergence as a dominant military power and rapidly industrializing state that was amassing vast overseas possessions, a pattern of expansion that would continue throughout the long nineteenth century. Britain was involved in a struggle for power with France, Spain, and Austria most especially beginning with the War of Spanish Succession, also known as Queen Anne's War (1702-1713), Jacobite rebellions in 1815-1816, 1719, and 1745-1746, ending with the battle of Culloden in 1746, when Scotland was firmly brought into the British rhelm, the War of the Quadruple Alliance in 1718-1720, War of Jenkins' Ear in 1739-1742, War of Austrian Succession (1742-1748), the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), Pontiac's Rebellion in North America (1763-1766), the Anglo-Mysore War in India (1766-1769), the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), further war in India against Maratha (1775-1782), followed by further war in India, and against the Dutch Republic from 1780-1784, and finally the French Revolutionary Wars from 1793-1802 and an uprising in Ireland in 1798. The fact that Vassa was enslaved to a British naval officer during the Seven Years' War inserted him into this long period of incessant warfare and was a major influence that shaped his life. British military dominance, despite setbacks in thirteen colonies in North America, was a factor arising from the virtually perpetual war footing. Vassa directly or indirectly was associated with major military figures. Despite his exposure in the Seven Years' War, the War of American Independence and again in the Wars of the French Revolution, he had little to say about world events, especially with respect to France, and yet he was an early member of the London Corresponding Society, whose radical members were sympathetic to teh French Revolution. Vassa was sometimes close to the center of power and almost always on its periphery, as is captured by his incidental acquaintances with Lord Nelson, William Pitt, King George III, Joseph Banks, and others.

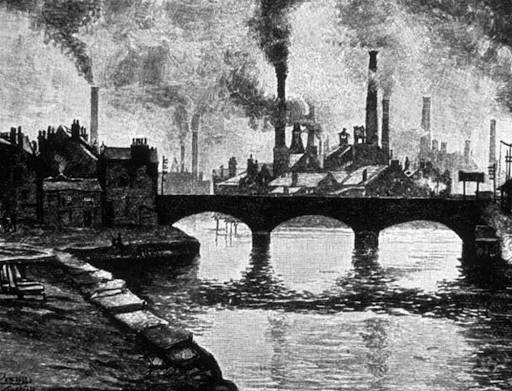

Vassa was also exposed to the industrialists and scientists who shaped the accompanying industrial transformation of Britain in the last third of the eighteenth century. His tour of Wales and Shropshire in 1783, well before he published The Interesting Narrative, took him to what became known as the Black Country in the area of the West Midlands, west of Birmingham, was a focal point of British industrialization, along with Shropshire further west bordering Wales and Staffordshire to the north. By 1785, the 23 km between Birmingham and Wolverhampton was one continuous urban zone with coal mines, coking factories, iron foundries, glass factories, brickworks and steel mills. The region was crisscrossed with canals that enabled transportation of industrial output. Alexander Blair, with whom Vassa was associated through his employment with Dr. Charles Irving, was a partner of James Keir, who together founded a chemical works and than a soap company at Tipton to the west of Birmingham in the Black Country.

At the same time as the industrialization of England, the enforced recruitment of enslaved Africans through the slave trade to the Caribbean and North America reached its apogee. First London, then Bristol and finally Liverpool expanded British involvement in trans-Atlantic slavery on an unprecedented scale. When the young Olaudah Equiano experienced the notorious Middle Passage in 1754, British merchants were already the leading suppliers of labor for the Americas, accounting for over 1,500,000 people from the 1750s to 1800, approximately 40 percent of the total number of Africans sent to the Americas. Without that recruitment of labor, British colonies simply could not have become one of the pillars of British economic expansion.

Vassa also participated in the commercial growth of Britain, another key factor in the economic take off that enabled the rise of Britain as a global power. Even before he gained his emancipation, Vassa was trading in the circum Caribbean world as an employee of a Pennsylvania merchant who had relocated to the Caribbean. After Vassa returned to England as a free man, he enlisted on ships trading to the Mediterranean and North America. He participated not only in the consolidation of Britain as the dominant naval force in the world through his military service but also in his capacity as a merchant and sailor on commercial vessels.

Vassa also benefited from and contributed to the intellectual and scholarly achievements of the era. Vassa skirted with, if he did not always interact with very distinguished individuals, and his slavery under a naval captain taught him protocol and language. His appreciation of the French horn, which he learned to play in London, provides a clue to his taste in music and hence the reason that he may have met Chevalier St. Georges, the French composer, appointed Director of the Paris Opera, who visited London when Vassa was there. Sympathetic to the French Revolution then underway and being of African descent involved in the abolition movement very well underlay a meeting, although there is no evidence that supports this supposition.

Phillis Wheatly is another mystery. They could have met in the early 1770s. When did Vassa first become associated with the Huntingdonians, with whom Wheatley was connected. In fact the Countess of Huntingdon had paid for Wheatley’s visit from Boston to London. Since we have no evidence of when or where Vassa joined the Connexion, it is tempting to think that there was a connection between Wheatley’s visit to England and Vassa’s conversion. Once again, Vassa joined the Huntingdonians because of connections with many key intellectuals in London who were Africans or of African descent. Grannisow, Marrant, Wedderburn and Wheatley stand out as leading intellectuals, all part of the Connexion and living and preaching within easy walking distance from where Vassa was living in London.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

This webpage was last updated on 2020-08-29 by Paul Lovejoy