Boston King

(c. 1760 - 1802)

Boston King was one of the first black loyalists and Methodist missionaries to settle in Sierra Leone in 1791, as well as being a prominent author. He was born into slavery on the Richard Waring plantation, 28 miles from Charleston, South Carolina around 1760 and worked as a house servant until the age of 16. His father had been enslaved in Africa. Waring became attached to him and trained him in management as a driver. His mother was a nurse and seamstress. When King was 16 years old, he was apprenticed to a carpenter, who treated him cruelly and inflicted frequent beating. King fled to the British when they occupied Charleston in 1780. After recovering from smallpox, a servant for several British officers prior to joining the army and working as a carpenter. He participated in a campaign through enemy lines to reinforce 250 besieged British soldiers at Nelson’s Ferry near Eutawville in South Carolina. He also served as a crewmember on a British man-of-war and was involved in the capture of a rebel ship in Chesapeake Bay.

As the war drew to a close, King, along with thousands of loyalists, sought refuge in New York City, the strongest post held by the British. King and other black loyalists were encouraged to work as servants for the British authorities. In 1781, King married a woman named Violet, a fellow runaway who had escaped servitude under Colonel Young of Wilmington, North Carolina. In late 1782, the Americans and British reached a preliminary peace agreement, which required the British to return all forms of American property, including enslaved Africans. This caused profound anxiety for King and other black loyalists who feared re-enslavement. British negotiator and commander-in-chief, Sir Guy Carleton, argued that this need not apply to black loyalists who were considered free at the time of the agreement. Carleton prevailed and King was among the 5000 black loyalists to be issued certificates guaranteeing their freedom. Between April 26 and November 30 of 1783, 3000 black loyalists departed for Port Roseway, Nova Scotia.

King, now 23, and his wife, boarded the ship L’Abondance and sailed for Port Roseway on July 31, 1783. They arrived at the Birchtown settlement on August 27, 1783. A muster held in January of 1784 showed that Birchtown had a population of 1,521 blacks, making it the largest free black settlement in North America. During the winter of 1783, various Methodist missionaries arrived in Birchtown, contributing to a great religious revival. The settlement became the largest Methodist society in Nova Scotia. King’s wife, Violet, was the first settler to convert to Methodism, inspired by the sermons of Moses Wilkinson, a black loyalist and Birchtown’s leading Wesleyan Methodist. In early 1785, King also converted. He began to preach across Birchtown and Shelburne. In 1791, he became the primary preacher for the black settlement at Preston near Halifax.

King had a strong desire to spread “the knowledge of Christianity” amongst his African brothers and in 1791, him and his wife joined a number of black Nova Scotians who were emigrating to the new colony of free blacks in Sierra Leone. A fleet of 15 ships left Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone in January of 1792. Shortly after arriving in Freetown, Violet contracted a fever and died. King survived to become the first Methodist missionary in Africa.

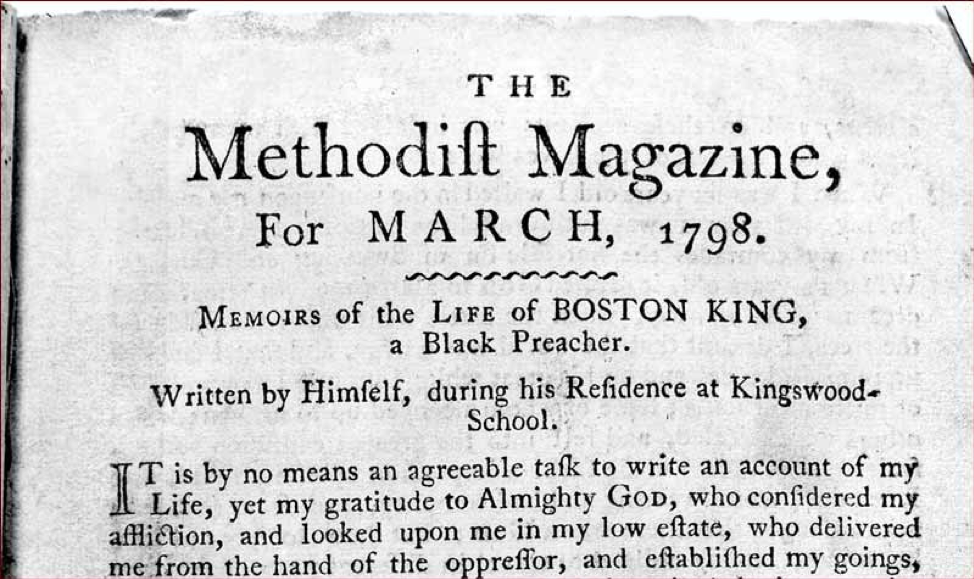

In 1794, King was sent to England to attend the Kingswood School near Bristol and improve his religious qualifications. He spent two years in England, during which time he published an autobiography in 1796, titled Memoirs of the Life of Boston King. It is one of only three autobiographies written by black Nova Scotians between 1600 and 1900. He returned to Sierra Leone in September 1796 to work as a teacher, although he soon became dissatisfied with his work. Around 1798, along with his second wife Peggy, King travelled one hundred miles south to become a missionary among the Sherbo people. The couple passed away in 1802.

It is unknown whether Gustavus Vassa and Boston King ever met. Like Vassa, King escaped the treacheries of slavery and wrote a biography about his life, although King’s memoirs did not receive the same degree of recognition as Vassa’s. Vassa was also a Methodist but of the Huntingdonian Connexion. As black men, Vassa and King were likely attracted to Methodism for similar reasons. Evangelical Methodists saw all individuals, regardless of their social stature, as sharing in salvation. While Huntingdonian Methodists such as George Whitefield did not outrightly condemn slavery, the Wesleyan Methodists saw slavery as wholly incompatible with Christianity.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Blakeley, Phyllis R. “Boston King: A Negro loyalist who sought refuge in Nova Scotia,” Dalhousie Review, (1968), 347-356.

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Walker, James W. St. G. “King, Boston,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography 5 (1983).

Whitehead, Ruth Holmes and Carmelita A. M. Robertson. The Life of Boston King: Black Loyalist, Minister and Master Carpenter (Halifax, NS: Nimbus Publishing Ltd., 2003).

This webpage was last updated on 18-April-2020, Fahad Q