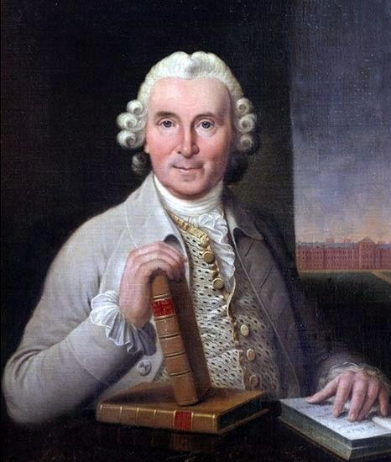

Dr. James Lind

(1716 – 1794)

Dr. James Lind was a Scottish naval surgeon known for conducting one of the first clinical trials on scurvy. He was born in Edinburgh on October 4, 1716 to a merchant, James Lind, and his wife, Margaret Smelholme, a member of an Edinburgh medical family. He became interested in medicine at an early age and after receiving his schooling in Edinburgh, at the age of 15 began an apprenticeship with a local surgeon, George Langlands. He never formally enrolled in medical school, as it was common at the time for students to attend individual lectures as they pleased. After he had completed his surgical apprenticeship, he was recruited by the Royal Navy in 1738 as a surgeons’ mate on a vessel commanded by Rear Admiral Nicholas Haddock. By 1739, he had completed his training and spent the next nine years working for the Royal Navy, sailing to the Mediterranean, West Africa, and the West Indies. In 1740, during the War of the Austrian Succession, he joined the crew of the HMS Salisbury, a 50-gun vessel captained by George Edgcumbe, the first Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, who later became the commander-in-chief of the Royal Navy at Plymouth. In 1747, he was promoted to surgeon. During a tour through the English Channel in 1747, the crew of the HMS Salisbury suffered a severe outbreak of scurvy. It was this experience that compelled Lind to retire from the Navy and return to the University of Edinburgh to pursue an M.D., having chosen venereal disease as the subject of his thesis. He graduated in 1748, received his license to practice in the city, and opened his own medical practice, which he ran for the next 10 years. He married Isobel Dickie and likely resided in an apartment in Paterson’s Court in Edinburgh’s old town.

In May of 1750, he became a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, to which he was elected treasurer seven years later. He also joined the Philosophical and Medical Society of Edinburgh. It was against the backdrop of a highly-publicized outbreak of scurvy on Commodore George Anson’s four-year circumnavigation of the globe that took the lives of 1000 men, as well as his own experience treating sailors with scurvy, that Lind published A Treatise of the Scurvy in 1753. In his treatise, he asserted that scurvy was a disease of improper digestion and excretion, worsened by environmental factors such as poor diet, air quality, and lack of exercise. He argued that it could be cured by the consumption of citrus fruit, coupled with a warm and dry atmosphere and a more readily digestible diet. His conclusions were based on a series of experiments that he had conducted in 1747 while on board the HMS Salisbury, in which he divided the crew of 12 into pairs and prescribed each a different treatment. The pair whom he prescribed oranges and lemons made a full recovery, while the others did not. Although it was already thought that citrus fruit could have an antiscorbutic effect, Lind was the first to systematically study such effects through controlled, clinical trials. It has since been suggested that these trials may have been falsified as the patients’ names did not appear on the ship sick list; nonetheless, his treatise provided an empirically-based method to compare medical treatments. Subsequent editions were released in French, Italian, and German.

In 1757, he published An Essay on the Most Effectual Means of Preserving the Health of Seamen in the Royal Navy. The following year, he left his Edinburgh practice and moved to Gosport to take up the post of chief physician to the new Yoal Naval (Haslar) Hospital at Portsmouth. During his time at Haslar, he continued to experiment and published multiple works, including Two Papers on Fevers and Infection in 1763, An Essay on Diseases Incidental to Europeans in Hot Climates in 1771, and a paper On Jail Distemper in 1773. His essays provided important contributions to the medical field regarding hygiene and nutrition and the prevention of diseases such as typhus on board naval ships. In 1762, he proposed a simple method of making sea water drinkable. His invention used musket barrels with large coppers to draw off the steam evaporating from boiling salt water. Lind got little credit for the apparatus, which was adapted in 1766 by Pierre-Isaac Poissonnier, a French doctor and chemist, and by Dr. Charles Irving, Gustavus Vassa’s employer. It is unknown whether Lind and Vassa ever met. There is some debate as to whether Irving stole or merely adjusted Lind’s distillation method for his own apparatus, which was adopted by the Royal Navy in 1770. In 1771, Irving invited Lind to a demonstration of his distillation method, during which time he was asked to sign a letter of support. At first, Lind was offended and refused to sign but eventually gave in, as he could not ascertain whether Irving had used the same musket barrel method as his own or if he had used a long thin tube wet with mops. Irving received £5000 from the government for his invention.

In 1783, after 25 years of service, Lind retired as the chief physician at Haslar hospital. His son John, who had worked as his assistant, took over his position. That same year, he was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, an organization created by the Royal Charter for the “advancement of learning and useful knowledge.” He passed away on July 13, 1784 at the age of 78 and is buried in the grounds of Portchester Church, where a tablet was erected in his commemoration.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Bartholomew, Michael. “Lind, James (1716-1794),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, published September 23, 2004.

Duffill, Mark. “Vassa Report No. 14A & 14B,” unpublished report, n.d.

Duffill, Mark. “Vassa Report No. 15: Part 1,” unpublished report, n.d.

Duffill, Mark. “Vassa Report No. 15: Part 2,” unpublished report, n.d.

Dunn, Peter M. “James Lind (1716-94) of Edinburgh and the Treatment of Scurvy,” Archives of Disease in Childhood 76 (1997), F64-F65.

Milne, Ian. “Who Was James Lind, and What Exactly Did He Achieve,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 105:12 (2012), 503-508.

Savours, Ann. “A Very Interesting Point in Geography: The 1773 Phipps Expedition towards the North Pole,” Unveiling the Arctic 37:4 (1984), 402-428.

This webpage was last updated on 2020-06-12 by Carly Downs