Thomas Wallace

Thomas Wallace was an Irish officer of the short-lived Province of Senegambia, Britain's first formal colony in Africa, established in 1765 and disbanded officially in 1783. The West African region stretched from the Senegal River in the north to the Gambia River in the south, hence the name "Senegambia." At the termination of the Seven Years War, the British consolidated its claims to coastal outposts in the region of modern Senegal and Gambia. The colonial status for the Province of Senegambia was modelled on British possessions in the Americas but never had a resident settler or merchant community large enough to implement the official mandate in West Africa. Senegambia was established with the goal of providing slaves for the Americas and industrial products, namely gum arabic, for Britain's textile industry. Thus those that immigrated to the Province were principally soldiers, occasional merchants, and criminals and rebellious sailors who had been exiled to the African coast.

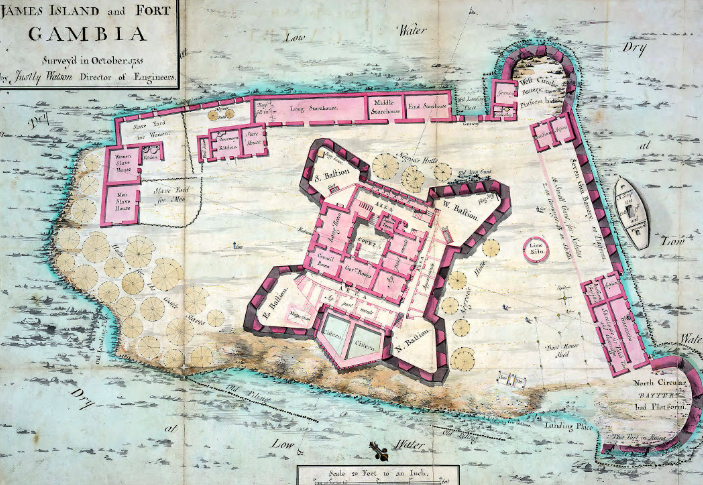

In 1763, Wallace was one of 54 individuals who lived on James Island, the main British trading post on the Gambia River, home to three civilian officers, eight European soldiers, 30 enslaved persons and their dependents. The officers on James Island were known to be illicitly involved in the slave trade. Matthias McNamara, the Lieutenant-Governor and then Acting Governor of the Province of Senegambia, resided on the island with Wallace. As Acting Governor, McNamara was described as a brutal man who inflicted heinous punishments on his subordinates. He imprisoned his adversaries in a six by eight-foot cell called the "black hole" under the stairs at James Island, one of whom being Captain Joseph Wall of Gore Island, his senior military officer. Upon his release, Wall brought two actions against McNamara, one for false imprisonment and the other for embezzlement. In an effort to discredit Wall, McNamara enlisted Wallace to lie on his behalf. In 1777, McNamara was charged not only with embezzlement and false imprisonment, but also subornation of perjury and illegal trading with the French. Wallace was also accused of subornation of perjury. The situation worsened for the two men when the Chief Justice of Senegambia, Edward Morse, accused them of conspiring against him. In June of 1777, a jury in Africa found there to be sufficient cause for the charges and deferred the case to the Board of Trade in London. In March of 1778, the council found the accusations to be true and recommended to King George III that McNamara and Wallace be relieved of their duties.

Despite his embarrassing downfall, McNamara continued to live a life of splendor in London. It was during this time that he developed a relationship with Gustavus Vassa, who was working as a barber in Haymarket. By March 11, 1779, Vassa's letters show that he was working for McNamara as a servant in his home, for how long is not known. McNamara took note of Vassa's religious devotion and recommended that he go to Africa as a missionary. Vassa was initially skeptical, having had a disastrous experience as part of Dr. Charles Irving's failed Mosquito Shore plantation scheme; however, he eventually came around. While it is unknown whether Wallace and Gustavus Vassa ever met, they were aware of one another through their mutual connection to McNamara. Both McNamara and Wallace submitted letters of recommendation on Vassa's behalf to the Bishop of London, Robert Lowth. Unfortunately the Bishop rejected Vassa's application. This was likely due to him being aware of McNamara's and Wallace's poor reputations and probably reluctance to send another missionary to Africa, especially during the war. After this point, Wallace's whereabouts are unknown.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Gray, J. M. A History of the Gambia (New York, NY: Barnes & Noble, 1966).

Lovejoy, Paul E. "The Province of Senegambia − An Early British Colony in Africa (1765-83)," in Lovejoy and Suzanne Schwarz, eds., Slavery, Abolition and Colonialism in Sierra Leone (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2014), 109-26.

This webpage was last updated on 2020-06-12 by Carly Downs