Reverend Henry Bromley

(1798 - 1878)

Reverend Henry Bromley was a Congregationalist minister and the husband of Gustavus Vassa’s sole surviving daughter, Joanna Vassa. Bromley was born in 1798 in Islington, London to a Protestant family with long-established non-conformist links. He was educated at Cambridge University, during which time he trained under Dr. Williams Harris to become a minister. He began conducting services in various churches in Cambridgeshire, including Trumpington, Horningsea, Landbeach, and Grantchester. It was likely at one of these churches that he met Joanna. It is well known that Gustavus Vassa was a religious man who had converted to Methodism and Joanna was likely a regular churchgoer. As a Congregationalist, Henry and Joanna would have been strongly anti-slavery. Although the decentralized nature of the religion prevented its churches from taking a united stand against the slave trade, few Congregationalists in England held slaves and, for the most part, they disapproved of the institution.

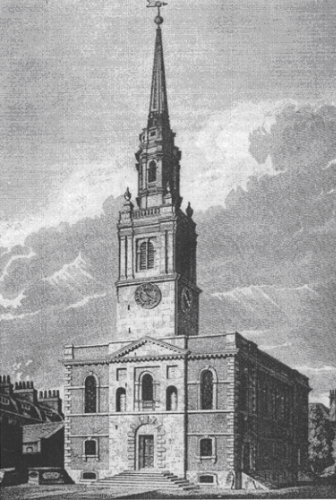

Bromley was ordained at the Independent Chapel in Appledore, Devon in June 1821. Two months later, on August 29, 1821, the couple were married at St. James Church, an Anglican parish church in Clerkenwell, London. At the time of their union, Joanna was 26 and Henry was 24. The two had lived separately prior to marriage. Joanna is believed to have been living with either Bromley’s sister or with relatives of John Audley, the co-executor of her father’s will, both of whom were witnesses at their wedding. At some point they moved to Appledore, Devon and resided there for the next five years. In 1826 or 1827, they moved to Clavering, Essex. Between 1827 and 1845, Bromley was a pastor at the Congregational Church, now the United Reformed Church. In 1829, he reported that there were 450 people in his congregation. During this time, there is record of his taking on a young boy named Joseph Harris as his apprentice; however, little else is known about his tenure as pastor. According to an 1841 census, the couple did not have children and likely never did. Bromley subsequently wrote a book on the Congregational Church and was involved in various local societies, including the Clavering Reading Society from 1827 until 1845, at which time he resigned from his position with the church. He cited his wife’s illness for his resignation, indicating that he had been very happy in Clavering. They both made their home in Harwich and at some point he took up a position as the minister at the Providence chapel there. It is not known the illness that she suffered from nor did The Church Book of the Protestant Dissenters in Clavering provide any further insight into his decision to leave the pastorate.

The couple subsequently moved to London, where Bromley became involved with the Provident Society for the Widows of Dissenting Ministers, otherwise known as the Widows Fund. In 1851, census records indicate that he was staying with James and Mary Dere, while Joanna resided in Stowmarket, Suffolk, likely at Henry’s father’s estate, due to her poor health. Joanna moved back to London several years later, while Bromley remained in Harwich making regular trips to visit her. He was not present at his wife’s death on March 10, 1857, although it is clear from the inscription on her tombstone at Abney Park Cemetery that she was loved and that he respected her African heritage. The inscription says: “Memory of Joanna beloved wife of Henry Bromley daughter of Gustavus the African…”

Bromley passed away 20 years later and was buried next to his wife on February 12, 1878. The Obituary mentions the love that his parents had for Joanna and remembers her father Gustavus Vassa, the African.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Dale, R.W. The History of English Congregationalism (Birmingham: Quinta Press, 2008).

Osborne, Angelina. Equiano’s Daughter: The Life of & Times of Joanna Vassa, Daughter of Olaudah Equiano, Gustavus Vassa, the African (London: Krik Krak, 2007).

This webpage was last updated on 2021-04-30 by Kartikay Chadha