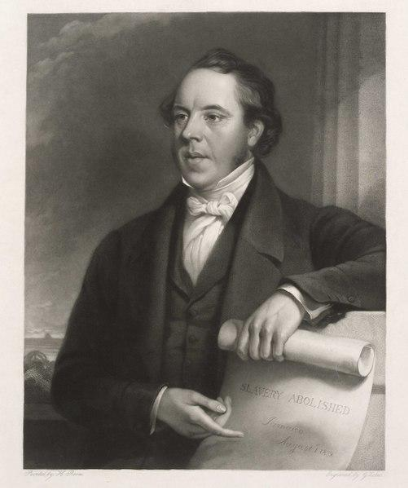

Thomas Clarkson

(1760 - 1846)

Thomas Clarkson, a prominent English abolitionist, was born on March 28, 1760, in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire. His father, John Clarkson, was a reverend and headmaster of the Wisbech free grammar school, and his mother, Anne Clarkson, was the daughter of an affluent family of physicians from Royston, Hertfordshire.

After completing his early education at the Wisbech grammar school, Clarkson attended the St. Paul’s school in Barnes, London, and was later admitted to his father’s alma mater, St. Johns College, Cambridge in 1779. Clarkson was described as an exceptional student, having secured several scholarships, and winning notable literary contests during his undergraduate years. While Clarkson graduated with a BA in mathematics in 1783, he remained at Cambridge to prepare himself for a career as a clergyman, evidently following in his father’s footsteps. Yet, after having won the Cambridge Latin essay prize in 1784, Clarkson felt a strong sense of ambition towards investigative writing and research and resolved to win the contest again in the following year.

Reflecting the most contentious issue at the time, vice-chancellor Peter Peckard, in charge of choosing the essay theme, selected the topic “Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare” (“Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?”). Though a young Clarkson initially entered this contest solely for the literary prestige, his analysis of the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade – particularly the Middle Passage, would fundamentally shift his own perspective of morality and justice, and would bestow in him a lifelong drive to campaign against the existence of the transatlantic slave trade, and at an ideological level, the entire system of slavery.

In the span of a few weeks, Clarkson read through a variety of texts on the topic of the slave trade, beginning with the Historical Accounts of Guinea written by Anthony Benezet, followed by Francis Moore’s Travels into the Interior Parts of Africa, which provided the subjective accounts of enslaved individuals. Included in the accounts was the story of Ayuba Suleiman Diallo, the son of a Muslim cleric who was abducted and sold into slavery. Sources also claim that Clarkson met and interviewed several individuals who experienced the horrors of the slave trade firsthand.

Clarkson won the essay competition and was invited to read his essay at the Senate House at Cambridge College. It was said that when he departed from Cambridge after his reading, he paused at a rest stop at Wades Mill, Hertfordshire, and contemplated the contents of his essay. “I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end.” (Clarkson, History, vol. 1). A small monument honoring Clarkson’s contribution was later erected on this very spot.

A translation of Clarkson’s essay was formally published by James Phillips in 1786, a Quaker from Wisbech who eventually became a close comrade to Clarkson. The essay quickly became a popular read in politically active religious circles, namely among Quakers, Methodists, and Baptists. The message of abolitionism had been gathering strength in Britain for a number of years, especially with Quakers. Though they could not occupy seats in Parliament – due to the prejudice against religious dissenters, they sought out sympathetic Anglicans for the very reason that Anglicans could sit in Parliament and influence political decisions. His essay also put him in contact with prominent political figures who were already publishing and campaigning against the slave trade, including James Ramsay, a ship surgeon, and Granville Sharp, a lawyer by trade. These individuals later came together to form an informal, non-denominational Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade on May 22, 1787. Their primary mission was to inform the public of the inhumane treatment of enslaved Africans, to campaign in favor of the abolition of the slave trade, and to eventually establish areas in West Africa where African-born and formerly enslaved individuals could live in freedom. William Wilberforce – a young, influential political activist, was recruited into the committee by Clarkson himself. All the original members of the committee were Quakers, excluding founding Anglican members Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp, and Phillip Sansom.

Following its formation, the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade published anti-slavery books, prints, and pamphlets and organized lecture tours in cities in England. This committee facilitated speaking opportunities for individuals who experienced the horrors of slavery first hand, namely Gustavus Vassa. On July 9, 1789, Clarkson wrote a letter of introduction on behalf of Vassa to the Reverend Thomas Jones, Master of Trinity College, Cambridge University. This letter was to recommend that Vassa be invited to deliver a lecture and advertise his autobiography at Cambridge University.

While the committee was opposed to the entire ideological system of slavery, they decided that attacking the transatlantic slave trade alone was a more feasible goal. Clarkson’s central duty was to seek out evidence that would support the campaign against the slave trade. Clarkson visited cities that were major slave trading ports, notably Bristol and Liverpool, where he faced opposition from supporters of the trade. In 1787, Clarkson was attacked and nearly assassinated by a gang of sailors in Liverpool. Unmoved, he published a pamphlet A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition in that same year and continued his lectures, including one at the collegiate church in Manchester.

The start of the French Revolution effectively transformed England’s “national temper” in 1789. Clarkson sympathized with the Revolution and spent five months in Paris from 1789 to 1790 trying to persuade the National Assembly to abolish the slave trade. At this point, as his health was rapidly deteriorating, he decided to retire, and nominated Wilberforce as the head of the committee.

During his brief period of retirement, Clarkson purchased an estate, took up farming, and married Catherine Buck in 1796 – a fellow radical whom he got to know through anti-slavery work. During this time, he also renounced the Anglican denomination, and appeared to favor the teachings of the Society of Friends, though he did not formally convert. In 1806, he published a short treatise, Portraiture of Quakerism, which was met with acclaim within the Quaker community.

By 1804, Clarkson rejoined the fight against the slave trade, and began once more travelling on horseback to gather evidence, until the slave trade was formally abolished in 1807. In 1808, Clarkson published an influential, semi-autobiographical volume, entitled History of The Rise, Progress, and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade. From 1808 onwards, Clarkson and fellow abolitionists continued to press the British Parliament to ensure that the abolition act was strictly enforced. In 1823, Clarkson joined the Anti-Slavery Society, committed to abolishing the entire system of slavery in the British Empire and the Americas, and remained as a key speaker. For the rest of his life, Clarkson was committed to the abolitionist cause and devoted much of his time to disseminating anti-slavery materials to the United States. On June 12, 1840, he gave the opening speech at the grand Anti-Slavery Convention in Freemasons Hall, and was the subject of Benjamin Haydon’s famous painting.

Clarkson died on September 26, 1846 at Playford, Suffolk. A large monument, designed by Gilbert Scott, was erected in 1880 in Wisbech, and in 1996, a tablet was placed in Westminster Abbey, between the statues of William Wilberforce and Stamford Raffles. The inscription reads: “a friend to slaves, THOMAS CLARKSON, b. Wisbech 1760-1845 d. Playford.”

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Brogan, Hugh. "Clarkson, Thomas (1760–1846), Slavery Abolitionist," Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, published May 19, 2011.

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-5545.

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Sapoznik, Karlee. The Letters and Other Writings of Gustavus Vassa (Olaudah Equiano, the African) Documenting Abolition of the Slave Trade (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2013).

This webpage was last updated on 18-April-2020, Fahad Q