John Marrant

(1755 - 1791)

John Marrant was a freeborn black American author and minister of the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. He was born on June 15, 1755 in New York City, but when his father died in 1759, he moved to St. Augustine, Florida, where he attended school until he was 10 or 11. His family then moved to Georgia and eventually settled in Charleston, South Carolina. He received classical training in the French horn and dance, spending two years to complete an apprenticeship in an unknown trade. In 1769 when he was 13, Marrant encountered the Calvinistic Methodist preacher, George Whitefield, and experienced his religious awakening. Whitefield was preaching open-air sermons in Charleston on his last southern tour. Marrant and a black friend attended one of Whitefield’s sermons with the intent of causing a disruption by blaring Marrant’s French horn so loud that the noise would drown out Whitefield’s preaching. However, Marrant was so taken by Whitefield’s sermon that he abandoned his disruptive intent. Three weeks later he confirmed his conversion to the distress of his family, which opposed his new-found religious devotion, which caused him to leave his mother’s home and set out on a journey into the wilderness.

Marrant found himself in Cherokee territory. Initially, he was not welcomed and was in danger of being executed, but the Cherokee eventually allowed him to live among them for two years. He became the first black missionary to the Cherokee and converted several of them to Methodism prior to returning to South Carolina. Upon the outbreak of the American War for Independence, Marrant joined the British Navy as a musician. He was involved in the 1780 siege of Charleston and the 1781 siege off Dogger Bank, where he was wounded. He was discharged in England where he obtained a job with a cotton merchant in London for three years. It was during his time in London that Marrant became a member of the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, a network of 64 dissenting meetinghouses that practiced Calvinistic Methodism.

In 1784, Marrant received a letter from his brother, one of 3,500 black Loyalists relocated to Nova Scotia after the war of American independence, in which he outlined the need for Christian knowledge within his community. This piqued the interest of the Countess of Huntingdon, who decided that she would send Marrant to Nova Scotia as a missionary. On May 15, 1785, Marrant was ordained in England at Vineyard’s Chapel, Bath, as a minister of the Connexion. He then became the first black Calvinistic Methodist missionary to be sent to Nova Scotia. After his arrival in Nova Scotia on November 20, 1785, he established a ministry of 40 families in Birchtown. His work extended beyond the black community, preaching to the Micmac and to black settlements elsewhere in Nova Scotia as well as a few white congregations. During his time in Nova Scotia, Marrant ordained two black men, Cato Perkins and William Ash, as preachers. He taught over 100 children in the Birchtown school, preaching four times a week. By late November of 1786, he had become exhausted with his schedule and relinquished control of the school and his congregation to his successors. In 1787 he travelled to Boston, shortly after returning to Nova Scotia to marry black loyalist, Elizabeth Herries, at the Birchtown Chapel on August 15, 1788. In 1789, he believed his mission in Nova Scotia to be fulfilled and returned to England. Perkins and Ash continued to spread the Huntingdonian cause; however, the congregation was depleted in January of 1792 when 1,200 Black loyalists left Halifax for Sierra Leone to join the settlement for formerly enslaved Africans.

Marrant is perhaps best known for his 1785 publication, A Narrative of the Lord’s Wonderful Dealings with John Marrant, A Black, an account of his experience with the Cherokee Nation and his Methodist ministry amongst the black loyalists of Nova Scotia. It appeared in at least 21 different printings and was translated into Welsh. The initial purpose of the narrative was to promote the missionary project in Nova Scotia, but Marrant transformed his account into an extraordinary tale of his captivity among the Cherokee. While some say the narrative is embellished, it, nonetheless, sold well. His struggle as a black man in a predominantly white country in which slavery remained legal, resonated within the literary world. It is also considered to be one of the most popular captivity stories ever published.

While it is unknown whether Gustavus Vassa and John Marrant ever met, they are considered among the most famous of early black writers. Marrant subscribed to Vassa’s second London edition in late 1789. The two authors also shared the same editor, the Reverend William Aldridge. As black men, Vassa and Marrant were likely attracted to Whitefield’s orientation of Methodism for similar reasons. Evangelical Methodists saw all individuals, regardless of their social stature, as sharing in salvation. The Calvinistic doctrine of predestination in which salvation was not dependent on charitable contributions or attendance at church was appealing to formerly enslaved Africans and freeborn blacks whose ability to perform such acts would have been severely restricted.

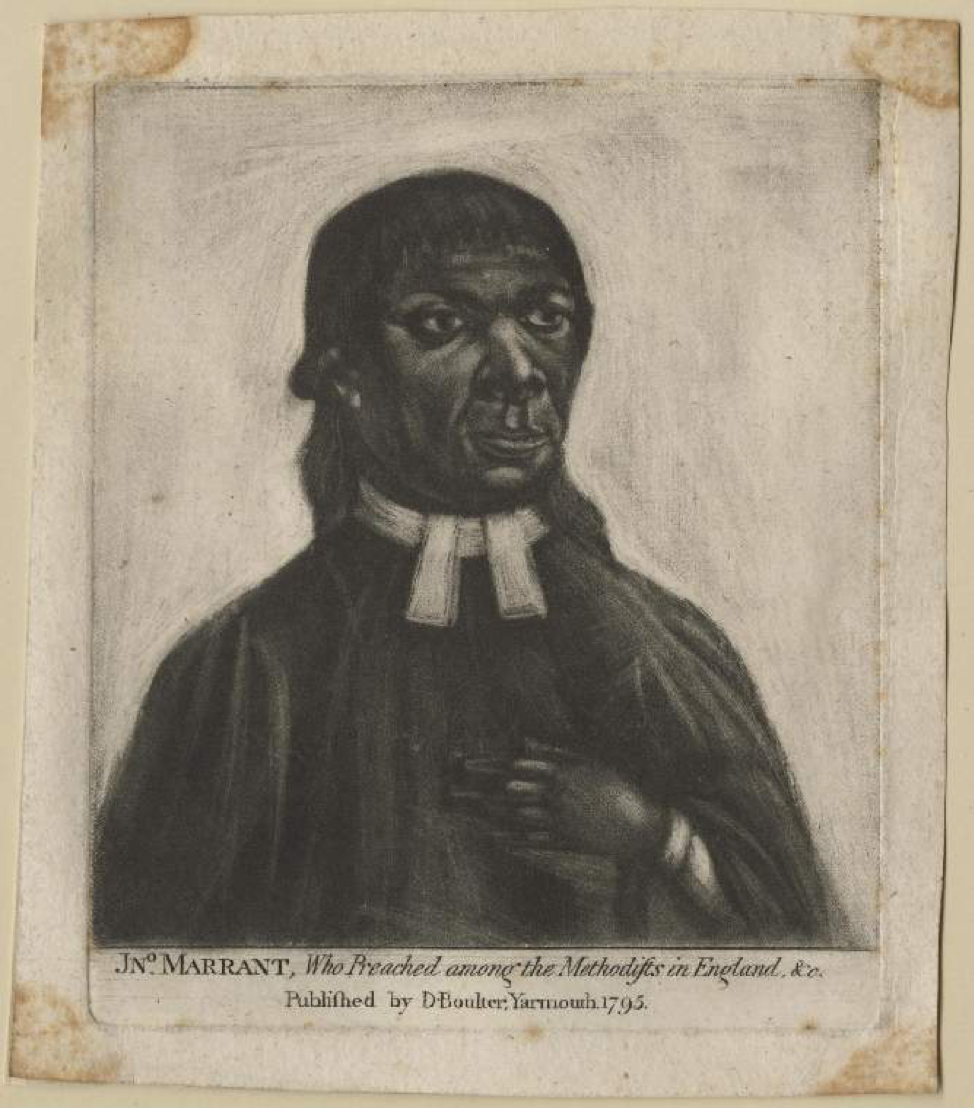

Marrant continued his ministry at the main Huntingdonian chapel in Islington until his death on April 15, 1791, at which time he was buried in the churchyard. After his passing, publishers changed the title of autobiography, omitting reference to his identity as a black man and lightening the colour of his skin in his portrait, likely wishing to avoid the controversy surrounding slavery and highlight the heroic story of Methodist progress.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Walker, James W. St. G. “MARRANT, JOHN,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography 4 (1979).

Whytock, J. C. “The Huntingdonian Mission to Nova Scotia, 1782-1791: A Study in Calvinistic Methodism,” Canadian Society of Church History (2003), 149-170.

This webpage was last updated on 18-April-2020, Fahad Q