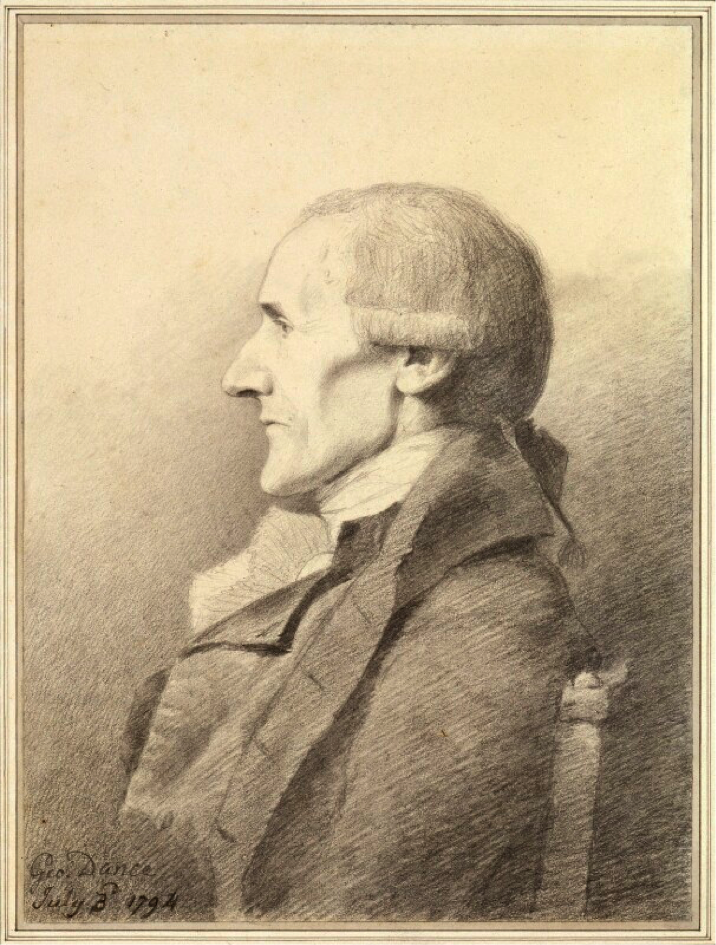

Granville Sharp

(1735 – 1813)

Granville Sharp, known as one of the earliest abolitionists, was born in Durham, England, on November 10, 1735. He was the son of the archdeacon of Northumberland and the grandson of the Archbishop of York, John Sharp. In 1757, he completed his apprenticeship with a Quaker linen draper in London and became a freeman of the City of London and a member of the Fishmongers’ Company. The following year, he was hired as a clerk in the Office of Ordnance in Westminster. In 1777, he resigned from his position after the office created a series of discriminatory policies directed at rebellious American colonies.

In 1765, Sharp moved to Wapping to live with his brother, William, who was a surgeon. On one occasion, a black man by the name of Jonathan Strong, sought out his brother’s services, having been badly beaten by his slaveholder, David Lisle. Strong was rushed to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital where he made a slow but steady recovery. The man subsequently told the brothers how Lisle, after having brought him to England from Barbados, had become dissatisfied with his services and proceeded to beat him over the head with a pistol and then left him for dead in the streets. It was not long before Lisle located Strong and hired two slave hunters to transport him back to the Caribbean. Upon hearing the news, Sharp took Lisle to court, claiming that Strong should be considered a free man. In 1768, the courts ruled in his favour.

From this point on, Sharp devoted himself to the abolitionist cause, fighting against British laws that designated enslaved persons as the property of the slaveholder on English soil. In 1769, he published A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery in England, a refutation of the Yorke and Talbot case, in which he presented legal and historical documents to suggest that slavery had no basis in English law and had always been illegal. This volume was the first of numerous books that Sharp wrote on the issue of slavery, the most notable of which include An Appendix to the Representation in 1771, The Just Limitation of Slavery in the Laws of God in 1776, and Serious Reflections on the Slave Trade and Slavery Addressed to the Peers of Great Britain in 1805.

As he became well-known in London’s African community, he was referred to other cases. In 1766 he took up the case of Mary Hylas and in 1770 that of Thomas Lewis. He was able to rescue both individuals from their slave masters; however, neither case resulted in a definitive ruling against slavery. In response to London’s growing population of poor blacks, he advanced the idea that free Africans should start a colony in Sierra Leone, which was supported by the British government. In 1786, Gustavus Vassa was hired as the Commissary Officer with the Sierra Leone expedition, perhaps due to his relationship with Sharp, who he had met in the late-1770s. Vassa was later dismissed for calling attention to corruption in the ship stocking process. The colony faced tremendous obstacles in settling and disputes soon broke out with the Koya Temne people from whom they had obtained land. In 1789, King Jimmy of the Koya Temne burnt the settlement to the ground.

In 1772, Sharp took up the case of James Somerset, an enslaved African who had been brought from Jamaica to England and, upon escaping servitude, was imprisoned on a return ship to Jamaica. After months of legal debate, Lord Mansfield, the Chief Justice of King’s Bench, ruled that Somerset was a free man and that a slaveholder could not forcibly remove an enslaved person from England. While the Mansfield ruling did not abolish slavery, it undermined it by denying slave masters the right to exercise their claims of possession, as enslaved Africans could legally obtain their freedom by escaping captivity. In 1774, Vassa called upon Sharp to help free a man named John Annis, whose former master, William Kirkpatrick, sought to illegally return him to the West Indies. This was likely the first time that Vassa and Sharp met. Several years later, in 1779, Sharp gifted Vassa a copy of one of his books. On a blank page within the book Vassa described Sharp as a “truly pious and benevolent man.” In 1780, Vassa wrote a letter to Sharp thanking him for his kindness, indicating that he had read three of Sharp’s treatises; The Just Limitations of Slavery & the Law of Passive Obedience (1776), The Law of Retribution (1776), and The Tract of the Law of Nature & Principles of Action in Man (1777). Previous to meeting Sharp, Vassa believed slavery could be reformed. Sharp’s treatises allowed him to see slavery for what it was, an inherently inhuman practice that must be abolished.

Sharp was also involved in making public the notorious Zong massacre, in which 133 enslaved Africans were murdered in order to claim insurance. Vassa brought the case to Sharp’s attention. In May 1787, Sharp joined Thomas Clarkson and other abolitionists in founding the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, an organization that was instrumental in achieving the abolition of the British slave trade in 1807. On December 15, 1787, Vassa, along with nine other men wrote a letter entitled “The Address of Thanks of the Sons of Africa to the Honourable Granville Sharp, Esq.,” commending him for his service to the black community, suggesting that his treatises should be collected and preserved. Of all leading abolitionists, Sharp was the most attentive to Vassa. He subscribed to multiple versions of his narrative and even went to see him on his deathbed prior to his passing on March 21, 1797. It is possible that on his deathbed, Vassa entrusted Sharp with the delivery of the money he had set aside in his will to build a school in Sierra Leone and that Sharp brought this money to the colony in 1798, although this is not confirmed. Sharp died on July 6, 1813. In 1820, Prince Hoare, an English painter and dramatist, wrote the Memoirs of Granville Sharp based on manuscripts, family documents, and material from the African Institution in London.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Fladeland, Betty. “Granville Sharp,” in Betty Lorraine Fladeland, ed.,Abolitionists and Working-Class Problems in the Age of Industrialization (London: MacMillan, 1984), 1-16.

“Granville Sharp (1735-1813): The Civil Servant,” The Abolition Project, accessed October 24, 2017. http://abolition.e2bn.org/people_22.html

Hoare, Prince, Memoirs of Granville Sharp, Esq. (London: Henry Colborn, 1820).

Paley, Ruth. “After Somerset: Mansfield, Slavery and the Law in England, 1772-1830,” in Norma Landau and Donna Andrews, eds., Crime and English Society, 1660-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 165-84.

Simkin, John. “Granville Sharp,” Spartacus Educational, published September 1997.

https://spartacus-educational.com/REsharp.htm *update whole reference

Wiecek, William M. “Somerset: Lord Mansfield and the Legitimacy of Slavery in the Anglo-Americans World,” University of Chicago Law Review 42:1 (1974), 45-68.

This webpage was last updated on 18-April-2020, Fahad Q