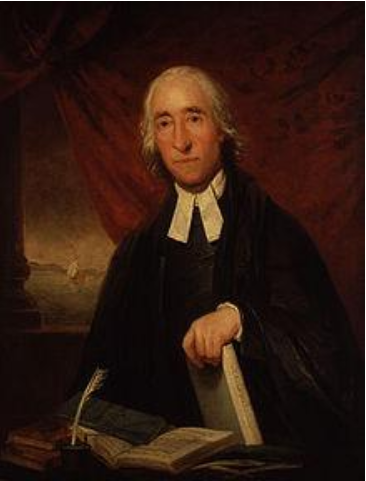

James Ramsay

(1733 - 1789)

James Ramsay, a prominent surgeon and abolitionist, was born on July 25, 1733 in Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire to parents, William Ramsay and Margaret Ogilvie. After attending Fraserburgh Grammar School, he completed an apprenticeship with a local surgeon. He then attended King’s College in Aberdeen, during which time he became interested in the teachings of Dr. Thomas Reid, a professor of moral philosophy. In June 1757, he enlisted with the army and joined the crew of The Arundel, a ship commanded by Captain Charles Middleton. On November 27, 1759 the vessel encountered the Swift, a British slave ship, transporting more than 100 captives. Upon boarding the ship to attend to the sick, Ramsay became so traumatized by the inhumane conditions of the slave quarters that he tripped and fractured his thigh bone. The injury left him lame for life. He subsequently returned to England and joined the church.

In November of 1761, Ramsay was ordained by the Bishop of London. He then travelled to St. Kitts where he acted as a minister and a doctor to local plantation owners. Here he met his future wife Rebeccca Akers, the daughter of a British plantation owner, whom he married in 1763, and with whom he had four children. During his time on the island, he witnessed first-hand the brutality of the punishments inflicted on enslaved Africans, tending to those who had been mutilated or nearly flogged to death by their overseers. Appalled by their mistreatment, Ramsay extended his religious and medical services to the enslaved, sparking frustration amongst local plantation owners who eventually boycotted his services. No longer able to earn a living in St. Kitts, he returned to England in 1777, and rejoined the navy as a chaplain to Admiral Samuel Barrington on the West Indies Station in April of 1778. During the latter half of 1781, he became the vicar of Teston and Rector of Nettlestead.

In 1784, he published An Essay on the Treatment and Conversion of African Slaves in the British Sugar Colonies, inspiring a generation of anti-slavery campaigners, including Gustavus Vassa. The book marked the beginning of a print war over the abolition of slavery, providing a moral and economic argument for the extension of human rights to enslaved Africans. He suggested that the emancipation of blacks would benefit plantation owners by creating a pool of self-motivated free laborers and consumers, a radical position also adopted by Vassa. In the same year, he published An Inquiry into the Effects of Putting a Stop to the African Slave Trade in which he proposed the development of an economy on the African coast for emancipated Africans to engage in trade relations with the British. While celebrated by anti-slavery activists, his books received harsh criticism from the planter community who launched attacks against him in various newspapers. He countered these attacks in his Reply to Personal Invectives in 1785. In May of 1789, the British Parliament began the debate on abolition under the leadership of Thomas Clarkson, William Wilberforce, and the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST). Ramsay was asked to prepare briefs for the debate, for which he included evidence that was supported by Vassa’s autobiography. He died shortly after. While he did not live to see the abolition of slavery, his intimate knowledge of Caribbean slavery and resulting influence supported the call for a parliamentary inquiry into the slave trade.

During her 57 years as consort, Queen Charlotte was unapologetically apolitical, managing to avoid court controversy. As Queen she was modest in her display and unassuming in her royal status and instead devoted most of her time to raising and educating her children and looking after the King. She was known as charitable, founding orphanages and homes for expectant mothers, as well as being Patron of General Lying-in Hospital (now known as the Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital). She was an avid music connoisseur and amateur botanist. King George III suffered periodic mental instability, especially after 1811, so that the latter part of Queen Charlotte’s life was spent caring for her husband until her death. Various places around the world have been named after her in her commemoration including Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Queen Charlotte Sound, New Zealand.

Gustavus Vassa sent a petition to Queen Charlotte on March 21, 1788, on behalf of the population of African descent in London. The petition, which was included in his autobiography, appealed to the Queen’s benevolence and humanity, asking for freedom from slavery. Vassa’s petition was influenced by the belief in the 18th century that she had African ancestry. This notion emerged after Sir Allan Ramsay painted a portrait, which supposedly revealed “African” characteristics, features which were not replicated in the portraits of later painters. Historian, Mario de Valdes y Cocom has determined that Queen Charlotte was a descendent of Margarita de Castro e Sousa, a branch of the Portuguese Royal House of Moorish background. Valdes argues that six different lines can be traced from the Queen back to Margarita de Castro e Sousa, thus explaining her “African appearance.” However, this is not conclusive, as the term “Moor” did not always refer to black Africans. However, Queen Charlotte’s attending physician described her in his diary as having “true mulatto features.”

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Rodriguez, Junius P. Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery: Volume I (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, Inc., 1997)

Watt, James. “Ramsay, James (1733-1789),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography last modified on January 3, 2008.

Watt, James. “Surgeon James Ramsay, 1733-1789: The Navy and the Slave Trade,” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 87 (1994), 773-776.

This webpage was last updated on 18-April-2020, Fahad Q