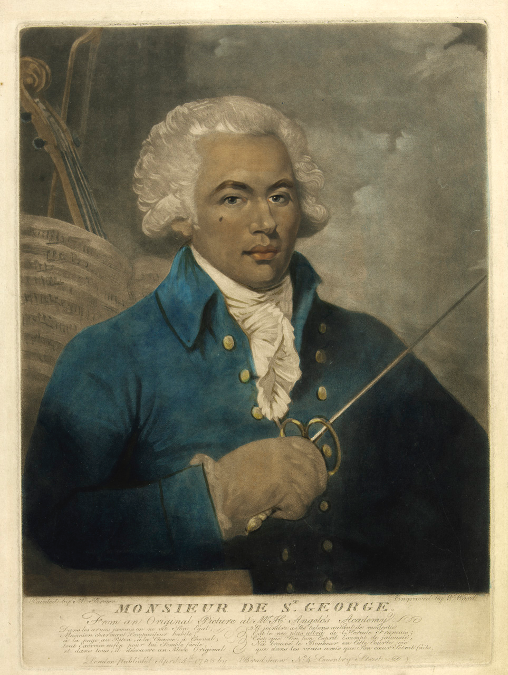

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

1745 - 1799

Joseph Bologne, Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges, was a famed musician, athlete, and soldier. He was given various nicknames such as “Le Mozart Noir” and “Le Don Juan Noir.” Although considered to be one of the greatest composers of the early classical period, having inspired both Mozart and Haydn, his work has largely been forgotten until recently. As one of the earliest musicians of the European classical tradition of African descent, Saint-Georges faced much adversity throughout his life. He was born in the French colony of Guadeloupe on December 25, 1745. His father was George de Bologne Saint-Georges, a plantation owner and slave master. While married, his father took an African mistress, a woman named Nanon who worked on his plantation, and who was likely born in Senegal. Saint-Georges was the product of this extra-marital affair. Given French miscegenation laws that barred children of mixed parentage from French noble status, it was unorthodox that his father acknowledged his interracial infidelity and provided full support to his son. In 1748, when Saint-Georges was two years old, his father’s wife, Élisabeth Merican, and his mother, took him to France after his father fatally wounded a man in a drunken quarrel. They arrived in France on January 4, 1749. His father, who had been sentenced to death, was fortunate to receive a pardon from King Louis XV while in France. On August 12, 1753, when he was 8 years old, Saint-Georges and Élisabeth sailed for Bordeaux on the ship, Le Bien Aimé. His mother joined them two years later and the family moved into a Parisian apartment. While slavery was permitted in French colonies, French law forbade it in France. Children of mixed-parentage were allowed to attend French schools. Saint-Georges received all of the schooling and training designated for young members of the French nobility. At the age of 13, he attended l’Académie royale polytechnique des armes et de l’équitation, run by Nicolas Texier de la Boëssière, an acclaimed swordsman. He became extremely skilled at fencing. One of his most well-known victories was against famed fencing master, Alexandre Picard, who had referred to his opponent as Joseph “La Boëssière’s mulatto.” He excelled in many other sports, including boxing, running, ice skating, swimming, and shooting. In addition, he studied literature, dance, the sciences, music and horseback riding. Saint-Georges graduated from the Royal Academy in 1766 and named an officer in the court of King Louis XV. From that point on, he was referred to as “Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges.” He went on to study violin under Jean-Marie Leclair the Elder, considered French’s greatest violinist and the founder of the French violin school. He later also mastered the harpsichord.

By age 19, Saint-Georges was well-known in Parisian society. In 1769, he joined Le Concert des Amateurs, an orchestra made up of the best noble and professional musicians in Paris, directed by Françios-Joseph Gossec. By 1772,he had written several symphonies and operas, mostly in distinctively French styles: the symphonie concertante (for a small group of instruments with orchestra) and quartet concertante (for a mixed group of small instruments). At one point, his compositions became so well known that he received equal billing with Mozart. Mozart has since indicated that he drew inspiration for his ballet score, Les Petits Riens, from one of Saint-Georges' melodies. In 1773, Le Chevalier de Saint-Georges took over as the musical director of Le Concert des Amateurs. In 1777, madame de Montesson, the former mistress and morganatic wife of the Duc d’Orléans, hired Saint-Georges as the musical director of her private theatre. As part of the position, he was given an apartment in the ducal mansion on the Chaussée d’Antin. It was during this time that Saint-Georges met Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart who also lived for more than two months.

In 1779, Saint-Georges and a friend were accosted by six men on the street. Fortunately, he was able to fight the men off without serious injury. The rumour at the time was that his attackers were secret police from the court in Versailles. Saint-Georges was allegedly targeted due to his friendship with Marie Antoinette, who had hired him to play music with her. He had been fired because they were deemed “too close,” although the Queen of France remained a supporter of his music. In 1781, Les Amateurs were forced to disband due to financial struggles. Saint-Georges appealed to his friend, the Duc d’Orléans, who helped him to re-establish the group under the name of the Concert de la Loge Olympique. He conducted its first performances in 1787 of the six “Paris Symphonies” of Franz Joseph Haydn, known as the greatest composer in Europe of that time.

Although he was afforded some privilege as the son of a nobleman, he was nonetheless a victim of racism. In 1775, the Paris Opéra considered Saint-Georges for the prestigious position of musical director; however, two of the company’s leading sopranos refused to work for a "mulatto” and petitioned the Queen. Saint-Georges fought for racial equality in France and England. He became involved with the growing anti-slavery movement in Britain and established a French abolitionist group called the Société des Amis des Noirs (Society of the Friends of Black People). As his fame grew and the public became aware of his involvement in the abolitionist movement, he was attacked by a group of five armed men in London. Fortunately, he was able to fend the men off using a stick as a makeshift sword. While there is no known connection between Saint-Georges and Gustavus Vassa, the two men were in London during the same period and must have crossed paths given their mutual involvement in the British abolition movement.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, Saint-Georges was vocal about his support for the revolution’s democratic aims. He became a captain in the National Guard in 1790 and in 1791 joined black Frenchmen who volunteered in the war between France and the Austrian monarchy. He became a colonel in the new corps, which was informally named the “Saint-George Legion.” The division was made up of 800 infantry men and 200 cavalry. Saint-Georges was recognized as a hero for his role in the defeat of the Austrian army at Lille; however, this prominence did not last for long. Shortly after, one of the deputies in the Saint-George Legion, Alexandre Dumas, a friend of the revolutionary leader Robespierre, accused him of corruption and mismanagement. He was imprisoned on these charges in 1793 and released the following year when Robespierre lost power.

On April 2, 1796, Saint-Georges went to St. Domingue, later Haiti. He became deeply disturbed by black-on-black violence on the island. When he returned to France on April 6, 1797, he became the musical director of Le Cercle de l’Harmonie, a new orchestra. The orchestra attracted large crowds and performed at the Palais Royal, the previous home of the Duc d’Orléans. Saint-Georges died from complications following a bladder infection on June 10, 1799. His contribution to the European classical tradition was largely forgotten until his works were rediscovered almost 200 years after his death. Some scholars have contributed this to concerted attempts during the reign of Napoleon to squash his music. Others attribute it to the public’s preference for the compositions of newer artists, such as Beethoven, Schubert, and Liszt.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Banat, Gabriel. The Chevalier de Saint-Georges: Virtuoso of the Sword and the Bow (Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press, 2006).

Crosby-Arnold, Margaret. “Joseph Bologne de Saint-Georges (1754-1799),” in Paul E. Lovejoy, ed., UNESCO General History of Africa: Global Africa (Paris: UNESCO, forthcoming).

Ribbe, Claude. Le Chevalier de Saint-George (Paris: Perrin Publishers Global, 2004).

This webpage was last updated on 2020-08-23 by Kartikay Chadha